I remember,

Slapping the book to my lap. ‘Why don’t you just leave,’ I would shout.

‘Just. do. something.’

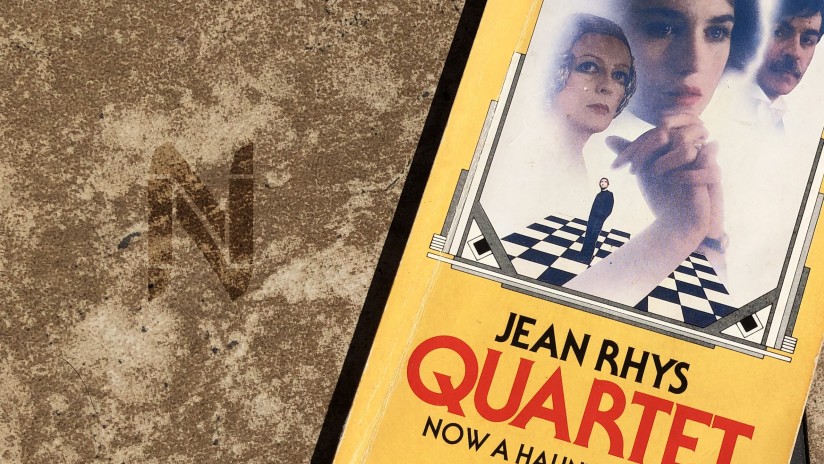

Marya, Jean Rhys, whoever you want to blame, can be an infuriating read. Something easy to feel when you sit in the shade of an oak tree in Tadpole Meadows. The reality is not so clear-cut.

That is what Quartet is. It’s not another poorly written female character, overwhelming with passivity. The narrator allows us to see (focalisation), her inner conflict, her resistance, and her eventual conclusion: her rationale for giving up – they won’t listen. It’s hard-hitting realism.

More so if you read around the book. It’s Jean Rhys’ story: a memoir with creative liberties and changed character names.

This is the early twentieth century, in the cosmopolitan heart of Paris – Montparnasse. The emotional vulnerability of Marya, her desire for intimacy and belonging, is established in just the opening pages. She walks down the Rue de Rennes and is reminded of Tottenham Court Road in London, home. Knowing only her husband, She desires the company of Anglo-Saxons as the solution to her problems. But the warnings are clear. The English “touch life with gloves on” and are always “pretending about something nice”. If she wants intimacy, the English are not the answer.

I was too sucked up in my infatuation for the Parisian lifestyle on my first read to notice the dangers or even the seriousness of the introduction’s mood.

It’s noticeable the lack of mobility between the communities. For a start, the characters speak in racial terms, preferring sometimes Anglo-Saxon over the more flexible English. Plus criticisms of the English and French dispel hopes for cosmopolitanism, or even truly belonging in either community; if the English are always reserved – touching life with gloves on – one is always kept at a distance.

Marya’s ethnicity is left ambiguous, potentially of mixed descent like Rhys herself. In the opening paragraphs, youths mistake her for one of their own, speaking to her in “unknown and spitting tongues”. This points to her perceived racial difference from the English. And this comes at a time when this mattered. When racial degeneration (or race in general) was on the minds of the English as you might see in Howard’s End. Will she find belonging with the English?

Her husband Stephan is useless, and his imprisonment for illicit art dealing for a year does not help Marya’s situation.

This should be a liberating moment for her. It was Stephan who stood in the way of her street wanderings, who “objected with violence” to these escapades down “sordid” streets. The one glimmer of hope for Marya was found on one of these streets, in a queer space, where the men were not reserved, but instead “bawled intimacies at each other”. And through the narration, we might understand Marya’s admiration for the patron’s makeup, where everything is done as it should be done, without a hint of a lack of experience. The cosmopolitan dream can be found down the sidestreets, somewhere which the political, marginalised subject is likely to discover.

This is possibly the strength of the flâneuse over the flâneur.

Moments like this haunt me in the aftermath of the book. After she found herself desperate for survival, forced into a sexual affair with Mr Heidler, manipulated into such by his wife, trying to save her marriage. Jean Rhys does not write a tale for women, but writes for a variety of political factors, which are all interlinked.

Rhys’ world is not so straightforward.

I can shout all I want.

But I’m not in the situation. And logic comes easier when removed like the reader.

Marya shouldn’t frustrate you as much as the society that leaves her immobile, unable to do anything other than to convince herself she loves Mr Heidler. After all, as admitted by the focalisation early one, “poverty is the cause of many compromises”, and without a family background to fall back on, the world is a very dangerous place.

The male hypocrisies should frustrate you. Marya is seen as a “hussy”, a “mince de poules de luxe” by all those that surround the Heidlers, while Mr Heidler is always greeted affectionately, without any loss to his reputation. Stephen, having left Marya without support, is infuriated by her affair, and goes to challenge Heidler – probably as the affair was at the expense of his reputation.

Marya protests. Marya is killed?

And that’s where it ends. Stephen sets off in a taxi, where his mistress waits for him.

The hypocrisy should be what infuriates.

The novella is damning for the men, who at every turn are remote and emotionally unavailable. What hope is there for the flâneur ideal? Stephen is very similar to the flâneur set out by Baudelaire: a collector of beauty, of which Marya was one. Heidler claims to love her, but what substance is there to it? The word seems empty. Marya seems deprived of any intimacy. If these are representative of the middle-class men of this society, then their accounts of the street life or people are meaningless. They can’t seem to understand anything beyond material value.

The flâneuse knew where to go, where to find the marginal communities of Paris. Stephen’s objections or Heidler’s remoteness, express no hope like the flâneuse promises for representing Paris at an intimate level.