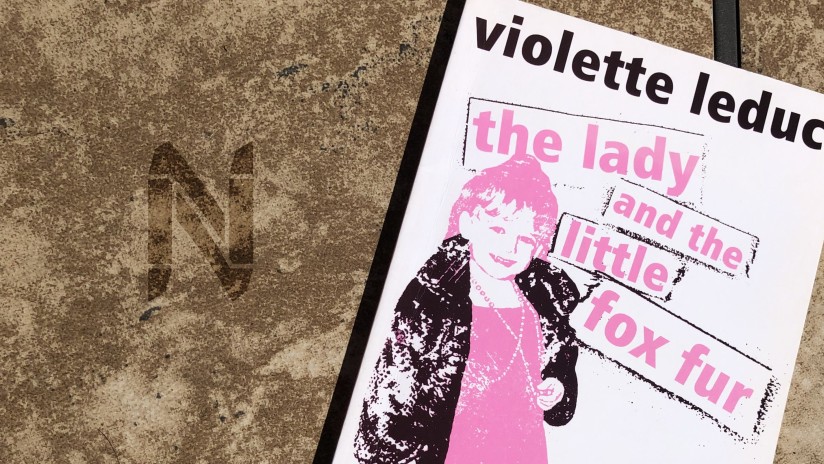

Leduc received admiration from some of the great French thinkers of the century, (De Beauvoir, Sartre, Camus, and Genet). I find it strange that more is not written on The Lady and the Little Fox Fur in this case. What a succinct image of a lonely, ‘mad’ woman, barely scraping by in a city of excess. And when I say ‘mad’, she is not the kind we pity and walk away from, for there is something loveable about her character. The way her room can come to life without the Leduc’s narratorial cogs grinding and sticking: the skirting board abuses her, her furniture turns on her. Nothing seems unnatural about it.

This is the kind of thing that also occupies me in my own writing as well as my reading. I’m always enchanted by the mystery of life. The few things I have written recently recall these surreal scenes; the Woolfian tendency to let realism fall apart and into the writer’s hand; the hole worked away by an insect in the skirting board can transform into a mouth, accusing the poor lady of betraying her room of things for bodily pleasures. Everything is semi-logical.

The complexity of Leduc’s Lady is that she both welcomes and resists the title of ‘mad’. Craziness implies a lack of sense.

Maybe we should walk on.

Ignore them, you say, they are speaking nonsense.

But should we? Is she not more lonely than crazy? Are the things talking to her, coming to life, just a coping mechanism or an advanced relationship with the things around her? Are these things, her room, just an externalisation of herself?

Let me explain.

When things take our fancy – the fox fur for her – does this not come from some desire within? It couldn’t be too improbable to say we can read a lot about one interior based on the things that take their fancy. We can be like archaeologists, take these things and ask what they tell us about one’s routines, habits, and interests.

Furthermore, I wear clothes to reflect my spirit. The Lady’s room of things is just the same in my eyes. When the room comes to life, there is nothing but her own voice, all the fragments of her being.

This scene in particular has resonated with me since I first read it in my first weeks in Exeter, feeling the pangs of hunger myself. It all unravelled before me once I learned of the phenomena of the flâneur. Suddenly, the scene of the room made sense.

By this point, the Lady has succumbed to dreams of wealth; bowed to desire and quenched her hunger, where once “nourishment […] from the crowd” was enough. Before she was satisfied just watching, refraining from personal pleasures or comforts. “Memories are comfy too”, we’re told.

If anything, the Lady is the perfect flâneur/flâneuse. She is practically invisible to those that surround her – she is far too old to be subjected to the male gaze, too poor to be acknowledged. Neither is she involved in her environment any more than mere observation. She melts into the city, which becomes an “extension of her own idleness”. The moment she breaks from her observational standpoint and recognises her mortal needs, she betrays her connection to the wider world. She breaks the freedom of the flâneur ideal.

For the most part she is free, unaffected by most things human. And that is exactly it, the ideal is inhuman. Lingering disbelief kept prodding away in my head. I dreaded the inevitable.

She can’t go on.

I would be tempted to call her a hero, if not for her deplorable situation. If you have read my article on the flâneur, you would understand my temptation. She translates the flâneur ideal into the only way it could exist for a woman at the time, into the flâneuse. But it is not achievable, unless one is not human. The lady is nothing we should strive to be. Moreover, it exists to speak for the state of women, but also to undermine the ideal. No one can be that objective. The body is always there.

Still, the temptation to make her a hero remains:

Companionship, for her, meant a man putting down his blowlamp on her bedroom table

Her room is her space. She literally has a room of her own (as set out by Woolf); both a place of creative freedom and, if we view the room as her identity externalised, a being defined by herself and not by a man. She keeps her economic independence. A freedom. But the one thing she does not possess, as was mentioned in A Room of One’s Own, is a stable income.

For a day at least, the Lady is free and achieves the ideal in probably the one way that was possible for a woman of the day. What other woman could be so invisible as the one without any money and too old to be captured by the male gaze? When her humanity became sickenly clear, I could only think that there was not long left for this poor woman.

And it seems I was right. She lays down, feeling so tired, fails to hear the familiar roar of the Metro – her reliable timepiece – and falls asleep (for good?).

The sad undertones of Violette Leduc’s novella should not discourage anyone from reading it. The character is so peculiar, introspective, and subject to habits that they achieve an unmatched character depth. It was an amusing read and, unlike some modernist and surrealist fiction, not too cryptic to make me stop or even want to stop in the flow of reading.

I highly recommend reading this in tandem with Quartet. The tones are vastly different, Rhys being more pessimistic. But they have a shared struggle. Both the Lady and Marya struggle with loneliness, desire the freedom to live Paris (with differing levels of ‘success’), and battle for self-determination in a male-dominated world.

None of this is meant to discourage the practice of flânerie.

Not at all. I’m sure we can use its failures to adapt it to a more sensitive, cosmopolitanism.

These novellas expose the flâneur/flâneuse’s subjectivity, despite their attempts to disembody themselves. Observation is a form of participation and is a process of interpretation. An experience is made by the body in the world.